My great-aunt Margaret died six or seven days shy of her 107th birthday. I fully give her “time served” credit for those few days, and claim she lived to be 107 years old. In her 90s, she still tended a garden, and she refused pharmaceuticals until her 100th birthday when she decided she probably should start taking her high blood pressure medication.

So many humans seek the secrets of a long life. As I age and spend more time with seniors, I sometimes wonder why. Old age is not for the weak or weary, and yet it often makes us just that—weak and weary. In her last years, after her 100th birthday, I only encountered Aunt Margaret at family funerals, dressed in her favorite pastel blue or pastel pink polyester pantsuits.

At a funeral for one of her nieces, her siblings and in-laws and life-long friends all long gone, she carried grief beyond what any of us could comprehend. “I don’t know why God chose me to see everyone else go before me,” she said. In addition to her hearing loss, her frailty, and her grieving in the present, the moment was also a reminder of all those already lost.

At my Aunt Sybil’s funeral, Aunt Margaret told me, “I think God has forgotten me.” How heartbreaking and soul-crushing to think that this good and kind woman, who had attended church her entire lengthy life, feared that God had forgotten to call her home.

My 91-year-old mother recently commented that she knew more dead people than living ones. I thought she was exaggerating — until she broke out her list of dead family and friends. I shivered, realizing I started a list just like that during the pandemic, gathering notes on previous losses to combine with the new all in one place. My list is half a page so far; Mother’s list goes on page after page after page.

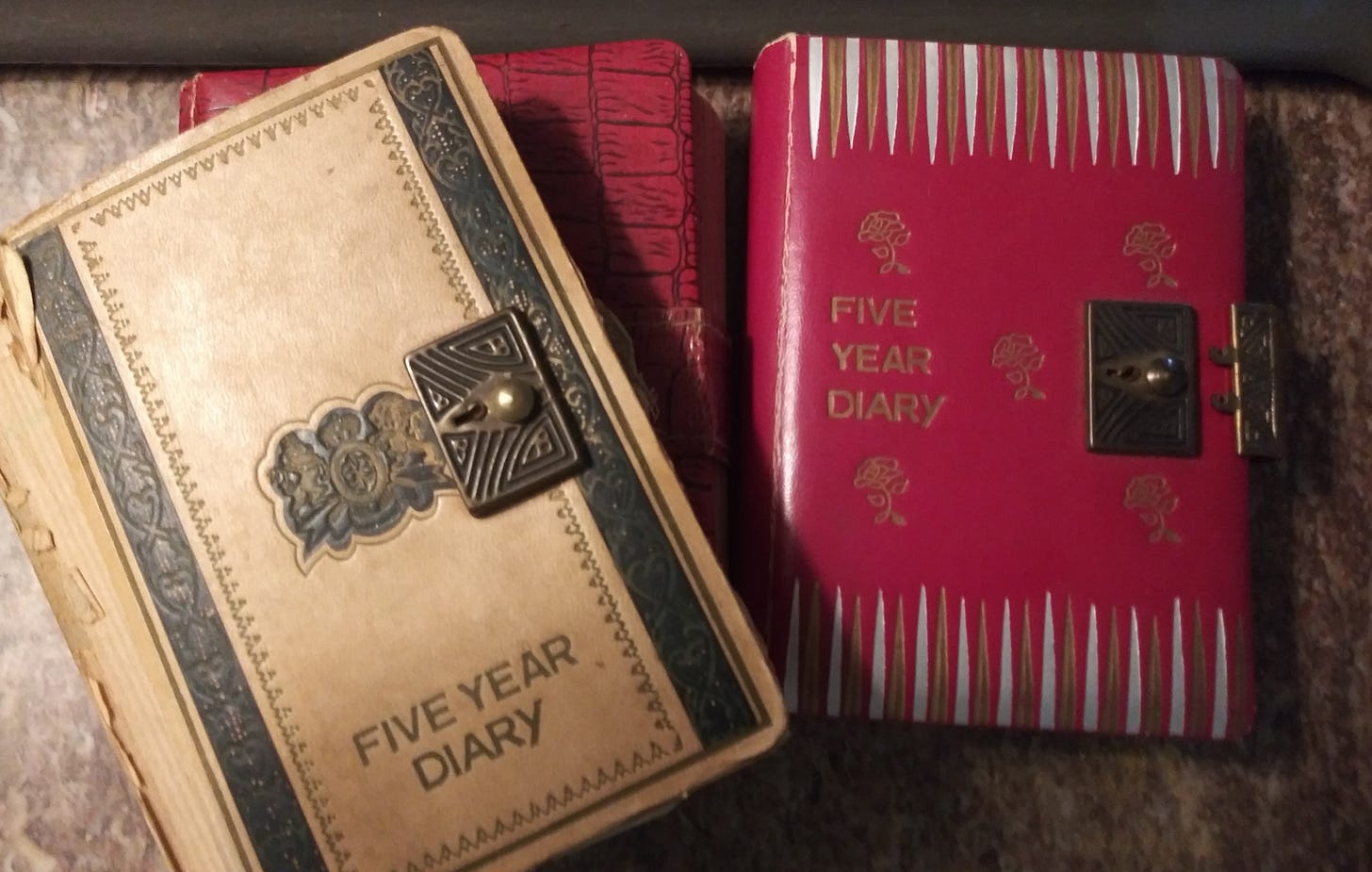

For most of her life, Aunt Margaret kept a diary. This summer, her daughter, Janet, gave me all the diaries found in Aunt Margaret’s house when they cleaned it out to sell it. They go back to the 1950s. Most of the books are five-year journals, five years in one, with five or six lines allotted per day.

Somewhere, within the pages, I perhaps expect to find the secrets of a long life.

I am reading the diaries in chronological order, having now read up to the mid-1960s. It is perfect bedtime reading, enough to put you to sleep in no time. Weather reports, chores completed, who visited, who was visited, how many attended Sunday School, how much was made at the bake sale, who died, how many canning jars were filled.

Yes, I come across an occasional nugget, like when they got their first television (and how often it needed repairing), when their church got heating units and disposed of the wood stove, when the Ohio River froze over, when local Union workers (including my Uncle Marion) went on strike or got laid off.

The diaries present no clear words of wisdom (though I expect to encounter more reflection in the record of her later years), but I do feel there are some lessons presented between the lines.

In the ten-plus years I have read so far, one phrase appears more often than any other. “I’m so tired I can hardly go.” The phrase reminds me that when she mentions doing her washing, the process included chopping wood, heating water, a washboard and/or ringer washer, and clothing hung on the line in nearly all weather. That jams and jellies were not purchased, but made, and strawberry pies included a day prior bent over in the strawberry patch.

(Aunt Margaret was so fond of strawberries, when she was eventually diagnosed with diverticulitis and advised to avoid eating seeds, she began peeling her strawberries with a potato peeler before she ate them.)

Only twice in what I have read so far has there been any sign of snark or drama. Because such comments are so rare in her life record, I wish someone living now could tell me what prompted the comment about my grandmother, Thelma, Margaret’s sister. Aunt Margaret wrote, “Thelma really showed herself today.”

Thelma was the sister who left the county life in Mason County and moved with my grandfather to the city of Parkersburg, where Grandpa opened and ran the main feed store downtown. Whatever happened occurred during a visit to their home in Parkersburg, and no more than a single sentence, a blip really, exists to show any evidence of kerfuffle.

The Wheeler women were workers. Their father was hit and killed by a drunk driver, and during their adult lives, the sisters rotated their dementia-riddled mother from one home to another. The second most noted sentence in twelve years of record is, “Mother is here.” As the years progress, my great-grandmother’s “fits” are also simply recorded — “She is so lost,” “I was up until 3 am with Mother,” “Mother went to Rays, but came back after two hours,” or “Mother has been in bed nearly all day.”

Once, Great-Grandma took off down the hill three times in a single day. I have no idea what hill, or where she was headed, but I get the impression she simply had this incessant urge to go somewhere. It doesn’t surprise me. Her daughter, my grandma Thelma, ran away from the nursing home more than once.

In fact, “going” seems to be a family characteristic. Right after writing “I can hardly go,” Aunt Margaret would note that they went to prayer meeting, drove someone to the doctor, or visited a neighbor. Even when she could hardly go — she still went.

Since the pandemic, I often feel like my “get up and go has got up and went.” And though I do not ever intend to be on the go as much as Aunt Margaret, nor feel any drive to go for no reason like my great-grandmother or grandmother, I understand the habit of recording the day’s simple accomplishments. And so, I have started my own little daily record.

“Lovely fall day, 50 degrees in the a.m. but warmed up nicely. Took a long walk with the dogs, piddled around outside in the sunshine, washed the dishes, and worked (online) for four hours. Finished Lips painting, started Spiral Staircase. Yolanda called, Christin called, wrote a poem, made Shepherd’s pie for dinner.”

Aunt Margaret didn’t write her diaries for us. She didn’t write for posterity or for an audience, or take note of daily trivia for anyone other than herself. Her spelling was not perfect, her scribbles in some places are unintelligible to anyone other than herself. Her journal was her record of daily accomplishments, daily challenges, and daily blessings.

I have found that simply recording my daily notes reminds me that I am living, that I am up and going. Even a day of trivial tasks is a day lived.

I believe in the benefits of journaling. So much, in fact, that I have written and presented several articles relating to the process. Perhaps my academic and scientific perception of the journaling process prevented me from seeing that journals need not be special, or themed, or complicated, or even creative. Five or six lines a day will suffice.

I encourage you to start there, with five or six lines a day. Your life is worth recording, if for no one other than you. And if your descendants get to also read the record of your days, it matters not if your spelling is off, or you go into detail. Your life is made up of small moments that become your life history.

My challenge to you is to write five lines a day — just the facts, nothing fancy. There are benefits large and small.

If you need any further convincing, consider the following articles from our online archives as well:

In addition, two articles from the print archives of Two-Lane Livin’ Magazine have been recently presented online:

And as we move towards the election and the upcoming winter, let’s take some time to look at our aging selves and laugh a little:

Thanks for reading ~

Lisa